Anthropology is the study of humanity via rational analysis and scientific enquiry.

It aims to provide a thorough and cogent understanding of how our species fits within the context of dynamic nature, biological evolution, and socio-cultural development.

Physical/biological anthropology, archaeology, cultural/social anthropology, linguistics, and applied anthropology are the five main, interconnected subfields that make up the subject.

The goal of anthropology is to gain a deeper understanding of and respect for the biological oneness, sociocultural variety, and evolutionary history of humanity.

The human being is seen by anthropologists as a dynamic and complex combination of social behavior that is learnt within a cultural context and genetic information that is inherited; symbolic language is what separates our species from big apes.

Anthropology studies things like genes, fossils, artifacts, monuments, languages, communities, and their cultures.

Both intra- and inter-disciplinary research are used in the holistic approach.

It includes data from history, psychology, paleontology, geology, and other specialized areas.

Generalizations concerning the genesis and development of our own species from distant hominid predecessors, as well as theories about the emergence of social systems and cultural adaptations, are all goals of anthropologists.

Anthropologists can now provide a better picture of humankind's natural history and domination over other species as a consequence of study conducted over many decades and the convergence of facts and ideas.

The field of anthropology, with the human person as its center of study, mediates between the scientific and social sciences while including the humanities.

Anthropology is a distinct area of study and a rich source for the pertinent application of facts, concepts, techniques, theories, and viewpoints due to its acceptance and use of biological discoveries, such as the DNA molecule, and its attention to significant ideas in the history of philosophy.

In the evolving contemporary human environment, substantial fields of applied anthropology have evolved, including forensic, medical, business, and advocacy anthropology.

Growing fossil evidence indicates that our distant ancestors originated in a diverse group of hominid species, which in turn split off from earlier ancient apelike animals that formerly roamed Africa.

Some hominid types developed over millions of years, while others became extinct.

Only our own species has survived human evolution to the current day, proving that it has been an unusually lengthy and difficult process.

How incredibly fascinating it would have been to have seen our earliest hominid ancestors struggling to adapt and survive in those perilous open forests and grassy savannahs in the distant past! Indeed, speculating on the outward and inside actions of these early hominids is fascinating: They saw the same stars, went through significant habitat changes, and undoubtedly found birth, illness, and death to be puzzling.

The languages of ancient civilizations have developed, changed, prospered, and then perished, much like the majority of species.

It is a challenge for anthropologists to recreate both the material cultures and social interactions of ancient communities.

The four great apes—orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, and bonobos—as well as lesser primates are also compared and contrasted by anthropologists.

We have discovered that our own species differs from these pongids more in degree than in type as a result of this investigation.

Humans may be more closely related to the four great apes than Huxley, Haeckel, or even Darwin himself could have predicted in the 19th century, based on fossil evidence suggesting apes, monkeys, and prosimians are our evolutionary ancestors.

The anthropological search is aided by ongoing scientific and technological advancements, notably in the areas of more accurate dating methods, DNA analyses, and computers for linguistic and cross-cultural study.

As a boy growing up, I acquired an enduring passion for movies.

I was introduced to apes, primordial life forms, and ancient civilizations via movies like King Kong (1933), Mighty Joe Young (1949), The Ten Commandments (1956), The Thief of Baghdad (1940), Quo Vadis (1951), and Unknown Island (1948).

On my inquisitive imagination, the moving pictures on the silver screen made lasting effects.

My interest in natural history expanded throughout my secondary education as a result of Charles Darwin's scientific hypothesis of organic evolution.

I also learned about the philosophical past on my own and became enamored with Aristotle and Nietzsche's theories.

I've had a philosophical bent my whole life, and as a college student, I loved learning about the great philosophers in Western society.

I conducted research on human craniometry as a graduate student studying anthropology, and I also liked reading the works of cultural theorists, especially Leslie A. White.

My diverse interests, which included anything from astronomy to religion, were given meaning and purpose within the framework of evolution.

Once more on my own, I learned that many influential intellectuals, including the early anthropologists, had been affected by Charles Darwin's writings.

I wanted to combine anthropology, philosophy, and evolutionary theory during my graduate studies in philosophy.

I was prepared to critically evaluate evolutionary explanations in international literature by this research.

The year 1959 has been a turning moment in anthropological history.

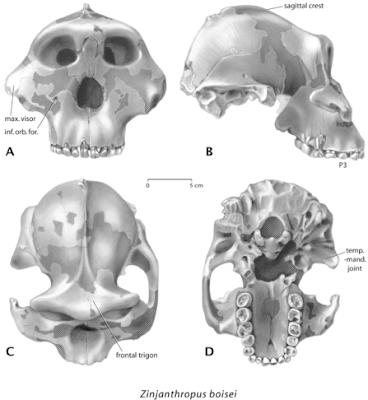

The "Zinj" skull was found in July by ancient archaeologist Mary D. Leakey in the lowest rock layers of Tanzania's Olduvai Gorge.

It was the earliest known example of a hominid in this region of the globe.

1.75 million years passed since Zinjanthropus boisei lived.

This exceptional specimen encouraged other scientists to look for hominid fossils and paleolithic artifacts in central East Africa, despite the fact that this species constituted an offshoot of human evolution that became extinct.

The origin, evolution, and variety of early hominids in Africa have been significantly clarified by other amazing discoveries made by scientists and scholars since the year 959.

My admiration for paleoanthropologists and ancient archaeologists who spend months or years looking for fossils and artifacts that provide light on the biocultural evolution of hominids rapidly grew.

It is understandable why some anthropologists are so possessive of their unique finds.

The start of long-term, up-close study of the wild apes in their native environments was another significant development in the middle of the 20th century.

Such meticulous investigations have tremendously aided comparative primate genetics study as well as monkey behavior research.

Their ground-breaking fieldwork has significantly advanced the fields of pongid psychology and biological anthropology.

Earth is both a museum and a cemetery.

Anthropologists discover more the more they look.

There are undoubtedly yet more fossil hominids and artifacts to be found.

Even undiscovered primates and ancient civilizations might yet be discovered in thick forests.

Anthropology is valuable because it provides science and philosophy with essential information and a broad viewpoint, but it is also valuable because it fosters tolerance and has application to our developing global species.

Although some anthropologists are now focused on finding solutions in the contemporary world, others are still interested in the biocultural development of people.

Future anthropologists will probably research how humans have adapted to life in space and maybe on other planets.

The 1968 movie 2001: A Space Odyssey introduced millions of people to evolution, just as it did for me.

Its captivating tale of the journey from ape to human to star kid incorporates concepts and images from works by Darwin, Freud, and Nietzsche, among others.

Both the cosmic viewpoint and an evolutionary framework were presented by Stanley Kubrick and Sir Arthur C. Clarke in a breathtaking visual style that is both fascinating and believable.

It is now essential for our species to have the drive to develop and the desire to absorb the knowledge that comes through evolution.

I sometimes imagine what it might be like to helm huge movies like Quo Vadis.

This "film" tells the human side of the five million year-long epic trip we've been on.

Find Jai On: Twitter | LinkedIn | Instagram

References And Further Reading

- Barnard, A. (2000). History and theory in anthropology. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Bass, B., & Jefferson, J. (2003). Death’s acre: Inside the legendary forensic lab— The Body Farm—where the dead do tell tales. New York: Putnam.

- Benedict, R. (1934/1959). Patterns of culture. New York: Mentor Books.

- Birx, H. J. (1984). Theories of evolution. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas.

- Birx, H. J. (1988). Human evolution. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas.

- Birx, H. J. (1991). Craniometry of the Orchid Site Ossuary, Fort Erie, Ontario. Buffalo, NY: Persimmon Press.

- Birx, H. J. (1991). Interpreting evolution: Darwin & Teilhard de Chardin. Amherst, MA: Prometheus Books.

- Boyd, R., & Richerson, P. J. (2005). The origin and evolution of cultures. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Chomsky, N. (1975). Reflections on language. New York: Pantheon.

- Corbey, R. (2005). The metaphysics of apes: Negotiating the animal-human boundary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Darwin, C. (1887/1958/2000). Autobiography. Amherst, MA: Prometheus Books.

- de Waal, F. B. M. (2005). Our inner ape: A leading primatologist explains why we are who we are. New York: Riverhead Books.

- de Waal, F. B. M., & Lanting, F. (1997). Bonobo: The forgotten ape. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Diamond, J. (1992). The third chimpanzee: The evolution and future of the human animal. New York: HarperCollins.

- Diamond, J. (2005). Collapse: How societies choose to fail or succeed. New York: Viking.

- Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (1940). The Nuer: A description of the modes of livelihood and political institutions of a Nilotic people. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fagan, B. M. (2005). World prehistory: A brief introduction, 6th ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Foley, W. A. (1997). Anthropological linguistics: An introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Fortey, R. (1998). Life: A natural history of the first four billion years of life on earth. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Fossey, D. (1983). Gorillas in the mist. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Galdikas, B. M. F. (1995). Reflections of Eden: My years with the orangutans of Borneo. Boston: Little Brown.

- Galdikas, B. M. F. (2005). Great ape odyssey. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

- Goodall, J. (1986). In the shadow of man. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Harris, M. (1968). The rise of anthropological theory: A history of theories of culture. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell.

- Harris, M. (1980). Cultural materialism: The struggle for a science of culture. New York: Random House.

- Langness, L. L. (2005). The study of culture, 3rd ed. Novato, CA: Chandler & Sharp.

- Larson, E. J. (2004). Evolution: The remarkable history of a scientific theory. New York: Modern Library.

- Leakey, M. D. (1984). Disclosing the past: An autobiography. Garden City, NJ: Doubleday.

- Leakey, R.E.F. (1984). One life: An autobiography. Salem, MA: Salem House.

- Leakey, R.E.F. (1994). The origin of humankind. New York: BasicBooks/HarperCollins.

- Malinowski, B. (1954). Magic, science and religion, and other essays. Garden City, NJ: Doubleday.

- Malinowski, B. (1961). Argonauts of the western Pacific. Bergenfield, NJ: E. P. Dutton.

- Manhein, M.H. (1999). The bone lady: Life as a forensic anthropologist. New York: Penguin.

- Mayr, E. (1991). One long argument: Charles Darwin and the genesis of modern evolutionary thought. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- McGee, J., & Warms, R. L. (Eds.). (2000). Anthropological theory: An introduction, 2nd ed. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield.

- Mead, M. (1928/1961). Coming of age in Samoa. New York: Morrow.

- Montgomery, S. (1991). Walking with the great apes: Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, Biruté Galdikas. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Moore, J. D. (2004). Visions of culture: An introduction to anthropological theories and theorists, 2nd ed. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira.

- Perry, R. J. (2003). Five key concepts in anthropological thinking. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall/Pearson Education.

- Powell, J. F. (2005). First Americans: Race, evolution and the origin of native Americans. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Radcliffe-Brown, A. R. (1922). The Andaman Islanders: A study in social anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Richardson, J. (2004). Nietzsche’s new Darwinism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sapir, E. (1921/1949). Language: An introduction to the study of speech. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Service, E. R. (1975). Origins of the state and civilization: The process of cultural evolution. New York: Norton.

- Tattersall, I., & Schwartz, J. H. (2000). Extinct humans. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Teilhard de Chardin, P. (1975). The phenomenon of man, 2nd ed. New York: Harper & Row.

- Thomas, E. M. (1989). The harmless people. New York: Random House.

- Turnbull, C. M. (1983). Mbuti pigmies: Change and adaptation. New York: Harcourt Brace.

- Turnbull, C. M. (1987). The forest people. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Turnbull, C. M. (1987). The mountain people. Riverside, NJ: Touchstone Books.

- Watson, J. D. (2003). DNA: The secret of life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Wells, S. (2002). The journey of man: A genetic odyssey. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- White, L. A. (1959). The evolution of culture: The development of civilization to the fall of Rome. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Whorf, B. (1956). Language, thought, and reality. New York: Wiley.

- Wilson, E. O. (1992). The diversity of life. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.